Saturday, December 23, 2006

Sunday, December 03, 2006

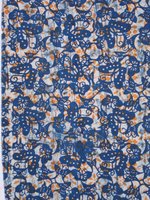

LIU DA PAO'S STENCILED FABRIC

LIU DA PAO'S stencilled tablecloths, wall hangings, cushion covers and quilts. They are all dyed in synthetic indigo using a soy flour and lime mixture. See the QuickTime video from November 16th, 2006

Posted by

M. JOAN LINTAULT

at

6:28 AM

0

comments

![]()

Thursday, November 16, 2006

LUI DA PAO

THE STENCIL

His paste ingredients are soy flour, lime and water. This paste is very gritty and not at all similar to Japanese rice paste. As a result Chinese stencils must be cut with larger openings to allow the less plastic paste to be deposited. Japanese rice paste is very elastic so the stencils are very fine. In the summer, after mixing, the paste can be used right away. In cold weather it should sit for a day before being used.

The stencils are made with paper soaked in tung oil. Tung oil comes from the seeds from a deciduous shade tree native to China. The seeds are rich in unsaturated oils.

Lui Da Pao uses natural indigo.

Posted by

M. JOAN LINTAULT

at

7:41 PM

1 comments

![]()

Wednesday, November 01, 2006

LANCAO-INDIGO FROM GUIZHOU

These fabrics come from Guizhou Provence in China.

They are dyed in indigo with a wax resist.

The wax on the cloth often cracks after it hardens. When it is dyed, the dyes seep into the cracks and make fine lines, which are called "ice veins".

These fabrics also come from Guizhou Provence in China. The patterns were made with a paper stencil soaked in tung oil to make it water resistant. The stencil is used with starch resist made from soy flour and

lime to make the design

lime to make the design

Posted by

M. JOAN LINTAULT

at

10:40 PM

0

comments

![]()

Friday, October 13, 2006

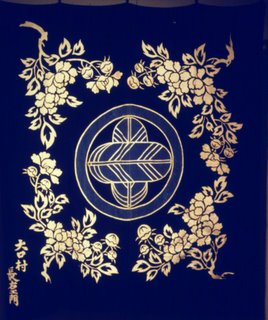

FUROSHIKI WITH KATAZOME IMAGES

Katazome (stencil printing using rice paste resist) using indigo with Sabracron H fiber reactive dyes. Sabracron dyes are Cibracron dyes repackaged by Pro-Chemical and Dye (1.800.2-BUY-DYE). I have been using Sabracron F for about about 25 years.

Sabracron F is designed to permanently dye cellulose fibers; plant-based fibers like cotton, linen, ramie, hemp, viscose rayon, jute, paper, wood, basket reed, and even silk using warm water, 105° to 120° F (41° to 49° C). It also dyes protein fibers, wool and silk using acid at a boil or with steam. Slightly less reactive than Pro Mix Reactive Dyes and very versatile with excellent wash and light fastness properties. This dye can be used for immersion as well as direct dye application. Colors range from pastel to very vibrant colors. These dyes can be kept in solution (without fixative) for two weeks at room temperature

Posted by

M. JOAN LINTAULT

at

2:59 PM

2

comments

![]()

Saturday, September 30, 2006

DYEING THE FUROSHIKI WITH INDIGO

Stenciled fabric on the rack. This drying rack is able to hold 3 pieces of 20" fabric or one long piece without touching the rice paste.

.

After removing the fabric from the indigo it will be green.

Detail of the rice paste

The fabric with the rice paste can be dipped up to 4 times before the paste begins to disintegrate. Ideally the fabric should oxidize for one day or longer between dips to get the best color.

The fabric with the rice paste can be dipped up to 4 times before the paste begins to disintegrate. Ideally the fabric should oxidize for one day or longer between dips to get the best color.

Rinsing the indigo and softening up the rice paste.

Brushing off and removing the rice paste

Finished furoshiki

Posted by

M. JOAN LINTAULT

at

12:30 AM

2

comments

![]()

Friday, September 15, 2006

Saturday, September 02, 2006

IKAT FUROSHIKI

Furoshiki with a double ikat, woven pattern. A Double Ikat is a weaving technique where the warp and the weft are tie-dyed before weaving. This technique leaves a seismographic line on the fabric where the dye has migrated under the ties. This technique requires a lot of skill as both the pattern of the warp and weft have to match.

The furoshiki has sashiko embroidery on the corners

Posted by

M. JOAN LINTAULT

at

7:19 PM

0

comments

![]()

Wednesday, August 23, 2006

FUROSHIKI BY SERIZAWA KEISUKE

(b Shizuoka, 13 May 1895; d Tokyo, 5 April 1984). Japanese textile designer. In 1916 he graduated from the design division of the Tokyo Technical College. Inspired by the bingata (multicoloured, stencil-dyed) textiles of Okinawa from 1928 he began to research them and, subsequently, the traditional textiles of other regions. His individualistic style of katazome (stencil dyeing) was the result of his involvement in the entire process, from design, stencil cutting and application to dyeing. He was deeply impressed by the writings on crafts by Muneyoshi Yanagi and contributed works to the MINGEI (‘folk art’) movement." Quote from "The Grove Dictionary of Art"

Posted by

M. JOAN LINTAULT

at

11:41 PM

0

comments

![]()

Thursday, August 10, 2006

FROM A SQUARE OF CLOTH

Silk furoshiki dyed with shibori, kankoko dots.

Batiste fabric, indigo dyed, stencil printed.

Cotton dyed with "Sabracron" fiber reactive dyes, then over dyed with indigo.

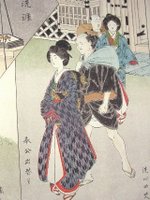

Woman and furoshiki

festival, Kyoto Japan.

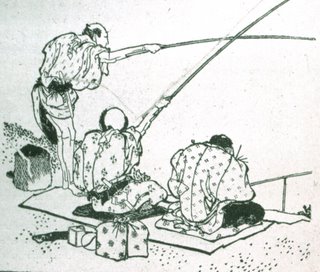

Illustration of fisherman

with furoshiki, from the

magazine "Art Interchange"

early 1900's.

Furoshiki used to wrap gifts and to transport items on the back. Meiji era book illustrations.

Posted by

M. JOAN LINTAULT

at

8:27 PM

0

comments

![]()

Wednesday, August 02, 2006

Wednesday, July 26, 2006

WRAP / ARRANGE / BUNDLE / CARRY / PROTECT / CLOTH = FUROSHIKI

A square piece of cloth made of any fabric. It comes in all sizes from one foot square to ten times that size. It is the most useful carrying invention imaginable. It has been used since the 7th century to carry every object, from elaborate gifts to lunches, vegetables, books or even bulky furniture.

SHORT HISTORY

Perhaps the original idea of a furoshiki was introduced from China. In the 8th century, the square of cloth used to wrap things up was called hirazutsumi. Shosoin, the imperial treasure house in Nara, has in its collection, cloth used for wrapping.

It is thought that hirazutsumi (just wrapping) might have been used in temples to store clothing, while bathing to purify the body before worshipping. In the 14th century, the practice of using hirazutsumi was also used by aristocrats as a method of wrapping their clothes. These hirazutsumi were decorated with family crests. The bathers in special, feudal, bath houses spread the cloth on the wet floors, placing their clothing on it and turning up the four corners over the center to keep the bundle together.

The first record mentioning furoshiki dates from the beginning of the 17th century. The word furoshiki originated from the public baths. During the early Edo Period, as the public bath, 0-Furo, was common to both men and women, they modestly entered clad in their underclothes. Each bather spread a hirazutsumi on the floor, much as a bath mat, and undressed on it. After bathing, they would wrap their wet underclothes and towels in the cloth to carry home. From this usage, the cloth became known as furoshiki, furo meaning bath and shiki meaning cloth or bath spread.

The convenience of the furoshiki, the simplicity with which it can be folded, placed in a purse, and used again and again, soon popularized it. The use of the furoshiki shifted from its original bathhouse use to the making of bundles for carrying goods, business documents, books, gifts , storing futon and for wrapping items during ceremonial occasions.

In Japan, the furoshiki has been the most popular method of carrying merchandise until the 20th century. A furoshiki can be carried on the shoulder, over an arm, in the hand, on the head or on the hips. Its specialized usage lead to the development of creative ways to wrap items. The Japanese have always been extremely dexterous with their hands, and in time the simple actions involved in the folding, wrapping or tying the furoshiki evolved into an important part of Japanese culture. A formal gift requires the closest attention to make sure that the container, wrapping and furoshiki fit the occasion for the gift they bear. This trait of evading directness, of keeping things under cover, has evolved from a very rigid social structure.

A characteristic peculiar to the Japanese is their abhorrence of carrying or storing things that are not covered. Even money must be wrapped in a suitable manner before it can be presented., regardless of how little the sum. A furoshiki wrapped item is a neat, creative way of packaging. The folding and stowing of the contents, are all done in a manner so as to please the eye, even after the packages have been opened. The versatility and convenience embodied in furoshiki are truly amazing in the manner they are employed. Objects of all sizes and shapes, thin, bulky, round, square or whatever, are easily accommodated in this piece of cloth which comes in a variety of sizes, but always in the familiar square shape. When not needed, it's simple to fold it up and tuck it into a handbag or pocket.

In the early days, the useful furoshiki was only a hemp or cotton mat. As time went on, and as the Japanese social structure became more complex and varied, the furoshiki assumed a more elegant and refined quality until the ultimate is produced in beautiful and gorgeous contemporary fabrics.

Today furoshiki come in a wide variety of materials. They can be made of silk or cotton, are often uniquely designed, woven and dyed with family colors, traditional crests or seasonal designs. Size and material depend on the purpose. Plastic furoshiki are used to protect merchandise from rain and dust. The furoshiki is a square piece of cloth made of any fabric, it comes in all sizes from one foot square to ten times that size.

The refined Japanese sense of color and all of the major trends of textile design are clearly stated in a study of furoshiki of the different eras. Masterpieces using the methods of Yuzen, Bingata, tie-dye, drawn silk and other artistic approaches to executing design are still to be found today. It is a treat to be able to browse through a shop displaying furoshiki, noting the various designs, from subdued to modern abstracts, eye catching colors and tints from the bright to the subdued

In Japan today, an occasional salesman can be seen lugging his wares in a furoshiki printed with his company's trade name in bold letters. Almost all Japanese cherish a memory or two of being summoned by their mother to greet a visitor in the living room and becoming excited to see what is in the furoshiki.

In the Edo Period, the well-dressed aspired to be shibui, smartly attired in an elegant manner. The furoshiki reflects this attitude very well in retaining its original purpose and practicality while evolving into a fine ornamental piece. Part of the joy of unwrapping a present contained in a furoshiki is that the furoshiki is revealed in its entirety. Attractive in concept and color, it offers a visual treat.

Now that the Japanese lifestyle has become so Westernized, furoshiki, the all purpose cloth, square, carry-all, seems to be giving way to the paper shopping bag. Although it is seldom carried today, the furoshiki in all its elegance and beauty, continues to be used on highly formal occasions.

Posted by

M. JOAN LINTAULT

at

10:14 PM

1 comments

![]()